Monday, June 22, 2009

Is this an orthodox restatement of the Golden Rule?

Please respond in comments.

Monday, June 15, 2009

What's the Deal with the Apocrypha?

What's the deal with the Apocrypha?

The Apocrypha is a collection of books written by Jews in the time between the testaments, that is, between Malachi (around 400 B.C.) and Christ (first century A.D.). The Jews at the time of Christ read these books in private, but they were not read aloud in the synagogues like the Old Testament was. Early Christians, like the Jews around them, read these books as well. Like the Jews, they also seem to have read them in private rather than in the church service.

It's important to know that Christians mostly used the Greek translation of the Old Testament (called the Septuagint) rather than the original Hebrew. The Apocryphal books and the New Testament were also written in Greek. So the Jews in the first century, who were arguing with Christians over religious doctrines, probably became very suspicious of any scriptures that weren't written in Hebrew. They stopped using the Apocryphal books not long after Christianity emerged.

Christians continued to read the Apocryphal books, however, and when they starting putting all the scriptures together in bound books (instead of collecting them on scrolls), they included the Apocryphal writings mixed in with the Old Testament. When the Bible was translated from Greek to Latin, the Apocryphal books were translated too. But when Jerome (an Italian monk who lived in Bethlehem and learned Hebrew) was asked to revise the Latin translation (in the 400s), he made a distinction between the Old Testament books and the Apocryphal books, which were "not in the canon." The Protestant Reformers felt the same way, but none of them seem to have felt it was appropriate to remove the books from printed Bibles. Luther did pull them out of their places interspersed throughout the Old Testament and set them between the Old and New Testaments. This was what the King James translators did as well. The stance of the reformers could be summarized with these words (from the Thirty-nine Articles of the Anglican church):

"And the other Books (as Hierome [Jerome] saith) the Church doth read for example of life and instruction of manners; but yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine; such are these following:" . . . and it goes on to list the Apocryphal books.

Catholics responded to this by rising up to defend the Apocryphal books, declaring at the Council of Trent that they were canonical, with the same authority as the Old Testament.

So when did the books drop out of Protestant Bibles? Well, the short answer is that it was easier and cheaper to print Bibles without the Apocrypha. The major driving force in putting Bibles in the hands of people from the 1800s on were the Bible societies. These organizations (think of them as the Gideons of that time) were made up of people from different denominations (Anglicans, Methodists, Presbyterians, Baptists, even Unitarians in the early days) who all wanted to make the Bible available. They all contributed money to the cause, but to keep everyone happy, they agreed that the money would only go to printing and distributing the straight Bible text—no notes or commentary. The Apocryphal books weren't considered part of the straight Bible text—they might be helpful reading, but they weren't important enough to print in these low-cost evangelistic Bibles.

Eventually, most Protestants lost familiarity with the books. They came to think of them as a Catholic thing, something to be resisted and argued against. But I don't think that's the right attitude to have. These books were, after all, written by Jewish believers, not by heretics or anything. It's probable that Jesus and the apostles had read them; the early church certainly read them; the Reformers read them. I'd argue that it won't damage a Christian's faith to read them. On the contrary, they can help us understand the world in which Jesus and the early church lived. They can probably teach us something about God and his dealings with his people, even if they aren't inspired and authoritative like the Old and New Testaments. There are a lot of books out there written by faithful believers, and we can benefit from them even if they aren't inspired. That's where I'd place the Apocrypha.

Works consulted:The NIV Study Bible, "The Time between the Testaments" (Zondervan, 1985)

The Book of Common Prayer

Introduction to the History of Christianity (ed. Timothy Dowley, Fortress Press, 2002)

Sunday, June 14, 2009

A Film Called Awful

Monday, June 01, 2009

Father Brown in the Excluded Middle

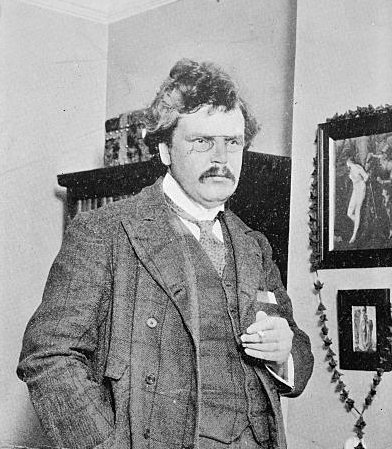

Happy belated birthday to Gilbert Keith. In his honor, I'll finally write this post I've been meaning to get to for months. It's inspired by an odd coincidence.

My biweekly reading group assignment was "The Blue Cross," the first Father Brown mystery. (Reading that is probably a better use of your time than reading the rest of this post, so if you leave now, I'll understand. Unless you're Anatoly Liberman, in which case, read on.) I had just read the assignment when Anatoly Liberman's Monthly Gleanings popped into my RSS reader. At the bottom of his post, Liberman returned to a well-worn topic, the use of they as a gender-neutral substitute for he.

A little background for those who don't read Monthly Gleanings: Liberman has made what I would call an aesthetic objection to they as a singular pronoun. The particularly ugly sentence he highlighted (from the Minnesota Daily, I assume) was "If a tenant has an eviction on their record, it does not mean they were a bad tenant."

A little background for those who don't read Monthly Gleanings: Liberman has made what I would call an aesthetic objection to they as a singular pronoun. The particularly ugly sentence he highlighted (from the Minnesota Daily, I assume) was "If a tenant has an eviction on their record, it does not mean they were a bad tenant."Liberman regards such grammar as "a horror." He also objects that it is inaccurate to defend it as a longstanding feature of good English. In the last two decades, some respected dictionaries (Random House, Heritage, American Oxford) introduced notes that claim a long and respectable pedigree (e.g., Austen, Thackery, Shaw) for singular they. Liberman might accept the example sentences ("To do a person in means to kill them") as good English, but makes a distinction between they with antecedents like person, someone, and anyone and its standing in for tenant, borrower, and fisherman. He challenged his readers to find examples of the "bad tenant" variety that predate the 1960s and 70s.

Still with me? Okay, here's the passage from "The Blue Cross" (1910) that a reader submitted in response to the challenge:

"There was one thing which Flambeau, with all his dexterity of disguise, could not cover, and that was his singular height. If Valentin's quick eye had caught a tall apple-woman, a tall grenadier, or even a tolerably tall duchess, he might have arrested them on the spot."

This is not precisely parallel to the "bad tenant" sentence. Chesterton did not write "If Valentin's quick eye had caught a tall pedestrian, he might have arrested them on the spot." But it doesn't fall into Liberman's other category. Chesterton did not write "If Valentin's quick eye had caught anyone particularly tall, he might have arrested them on the spot." What we have here is a tertium quid, an unjustly excluded middle: them stands in for regular old nouns like apple-woman, grenadier, and (or?) duchess, though not as blatantly as it did for the bad tenant.

Inexplicably, Liberman demonstrated no interest in this fascinating specimen. He dismissed it with a single sentence: "Surely, them does not refer to the apple woman, duchess, or grenadier separately." I was shocked. "On the contrary," I thought, "surely them must refer to these three separately! It cannot refer to them collectively, can it? It is precisely the indeterminacy of the gender (whether because of the mixed group or the possibility of masquerade) that prompted Chesterton to use them in place of him."

A few hours later, as I joined my colleagues—all of them veteran copy editors—to discuss "The Blue Cross," I pointed out the sentence and asked them about it.

"If the nouns were changed, would the sentence still make sense?" I asked. "Let's say it read:

'If Valentin's quick eye had caught a tall apple seller, a tall grenadier, or even a tolerably tall duke, he might have arrested them on the spot.'"

The copy editors wrinkled their noses and shook their heads. "It would have to be 'arrested him,'" one responded. The others agreed.

Notice that this verdict both confirms Liberman's initial disdain for the "bad tenant" sentence (if the copy editors had liked "bad tenant" sentences, they would have accepted my emended "Blue Cross" sentence) and challenges his dismissal of the original "Blue Cross" sentence. There is room for the case against the frivolous extension of singular they, especially when the referent's gender is known. But I believe the "Blue Cross" sentence shows that when gender indeterminacy is forefronted in the speaker's mind, using they is a handy and longstanding tactic, even for ordinary nouns. As Chesterton shows, it can even lend itself to rather elegant writing.